Boston Common, Boston, Massachusetts

Boston Common was the colonial town's "common pasture land," to which any citizen could bring cattle—and still can. Today it's Boston's central park.

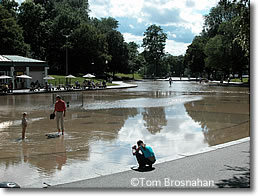

Kids play (and parents photo)

in the cooling waters of the Frog

Pond on

Boston

Common on a hot summer day.

Many colonial towns preserved a central public square for markets, meetings and militia drills, but Boston, founded in 1630 and soon the largest settlement in New England, had none.

Pasturing cows was more important to these early settlers.

During its explosive growth in the 19th century, Boston's government was smart enough to hire famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, creator of New York City's beautiful Central Park, to make a master plan for Boston's green spaces.

Olmsted's masterpiece was the "Emerald Necklace," a chain of green spaces, old and new, from Boston Common and the newer Public Garden at the heart of the city, along Commonwealth Avenue in the Back Bay to the Back Bay Fens, and finally to the Arnold Arboretum, miles from the center.

Olmsted beautified the Common, preserving a colonial and early American cemetery near the corner of Tremont and Boylston streets, but adding statues, monuments and a Frog Pond that serves as a wading pool and fountain for children in summer, and an ice skating rink in winter.

The ordinance allowing any Bostonian to pasture a cow on the Common is apparently still in the lawbooks, though a stroll through the Common on any summer day reveals picnickers, sunbathers, soapbox orators, street buskers, pitch persons and plenty of pigeons, but no cows.

The entrance to the MBTA subway's Park Street Station at the corner of Tremont and Park streets is Boston's unofficial "speaker's corner," where ideologues hold for on their political, social and religious beliefs—those, at least, who have not become bloggers instead.

The Massachusetts State House (capitol) tops Beacon Hill at the Common's northeastern corner, and the Public Garden adjoins on the west side.