New England Architecture

After almost four centuries of architectural evolution, New England has a lot of fine, beautiful buildings

Henry Hobson Richardson's Trinity Church (1877) in Copley Square, Boston MA.

Colonial Style

The colonists built simply and functionally, but these early styles have their own beauty.

The early colonists who came to New England brought no visions of grand mansions or stately churches. Their homes were simple, as befitted a people of strict religious beliefs. Here's an example, the Jethro Coffin House (1686), first house built on Nantucket Island:

New England colonial public buildings usually consisted of the meetinghouse (what others might call a church). This, though larger, was simple as well.

New England preserves a remarkable number of buildings from colonial days. For a look at buildings remaining from the 1600's, visit the Hoxie House (1637) in Sandwich, on Cape Cod, or the Whipple House (1640) in Ipswich, on Cape Ann, north of Boston.

Plimoth Patuxet Museums, near Plymouth, Massachusetts, gives perhaps the best glimpse of life and architecture of New England in the 1600s.

Whipple House (1677), Ipswich MA.

Georgian Style

Called Palladian in London, the designs of Christopher Wren and Inigo Jones crossed the Atlantic and became Georgian.

After the great fire of 1666, London was rebuilt in Palladian style by Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren. This updated classicism, called Georgian in America, appealed to colonial New England's builders, who happily used Wren's designs in building some of the region's most famous and stately churches.

America is a rich land of great potential, and it wasn't long before it yielded prosperity for the colonists who moved here from Europe in the 1600s and 1700s.

Along with prosperity came the gradual abandonment of the strict and ascetic religious life of the 1600s that had helped the early colonists to survive the rigors of settlement and exploration.

Prosperity allowed more beauty, style and comfort in life. In the 1700s, New England's colonists naturally looked to England for models of how to design public buildings appropriate to their new-found prosperity.

What they saw in architectural books of the time, and on their trading trips to London was the updated classicism of Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren, called Palladian style after Andreas Palladio (1508-1580), an Italian architect who "updated" the classical proportions and ornaments of ancient Roman architecture.

Because the occupants of the English throne in the 1700s were all called George (from King George I in 1714 through King George III [1760-1820]), the style became known in New England as Georgian.

Nearly every New England town that prospered in the 1700s and early 1800s has at least one fine Georgian church, and often two or three. With their tall steeples, classical facades, gleaming white exteriors, and many tall windows (some the famed Palladian window), these beautiful wood-frame buildings are graceful ornaments and an enduring symbol of New England's townscapes.

The updated Roman classicism of Georgian style was also used in buildings of brick and stone, as at Harvard University in Cambridge MA, which is a riot of Georgian red brick, classical trim, and gold-topped cupolas.

Georgian style was not just for public buildings. Georgian houses were built up to the time of the American Revolution, and in beautiful Litchfield CT until the end of the 1700's.

First Congregational Church in Old Lyme CT, a fine example of a New England Georgian church.

Federal Style

Domestic Federal architecture was straightforward and commodious: large rectangular two-story wooden buildings with rows of windows, chimneys at both ends and a grandish portal centered in the facade.

With political independence in New England came even more prosperity.

The shipowners and merchants of New England's great maritime ports—Salem MA, Portsmouth NH, and Providence RI, for example—wanted large, comfortable, imposing houses, and local architects gave them just what they wanted in the years following the Revolution.

The famous Charles Bulfinch, who designed the State House (Massachusetts' state capitol), on Beacon Hill in Boston, is New England's most famous Federalist architect.

Lesser-known Samuel McIntire of Salem left his indelible imprint on the older streets of his home town.

In Providence, College Hill boasts many handsome Federal-style houses.

Ralph Waldo Emerson House, Concord MA.

Ralph Waldo Emerson House, Concord MA.

Greek Revival

Spacious domes, soaring columns topped by Ionic capitals, and noble echoes of the Doric order—this is Greek Revival. The rage for the classical left fewer buildings in New England than in other states, which makes the remaining ones all the more worthy.

Sometimes called Classic Revival to include Roman as well as ancient Greek architectural elements, this style began to appear in New England cities and towns in the early 1800s, having made the leap from Europe, where it was commonly known as Neoclassical.

The revival of classic orders in Europe was a reaction to the decorative excesses of Baroque and Rococo design on that continent. (New Englanders were not building lavish public buildings until after the Baroque period had passed.)

The style also came into vogue as the early 1800s were the beginnings of the science of archeology. The great buildings of ancient Greece and Rome were being unearthed, studied and copied.

Americans saw themselves as the successors to the founders of democracy, and wished to echo the simplicity, solidity and monumental character of their buildings in their own.

Symmetry and lack of ornamentation are marks of the Greek Revival style.

Greek Revival is sometimes distinguished from Neoclassical architecture, popular in New England from the late 1700s through the 1800s, which is stricter in its adherence to the classical orders.

Boston's Quincy Market building (1825), now the centerpiece of Faneuil Hall Marketplace, is perhaps the best-known example.

Beneficent Congregational Church (1810) and The Arcade (1828) in Providence RI are other good examples.

For fine specimens of New England domestic Greek Revival architecture, visit some of the oldest towns in Vermont, particularly Grafton, a veritable museum of the style carefully preserved by its sensitive residents.

Quincy Market (1825), Boston's most famous Greek Revival building.

Neoclassical

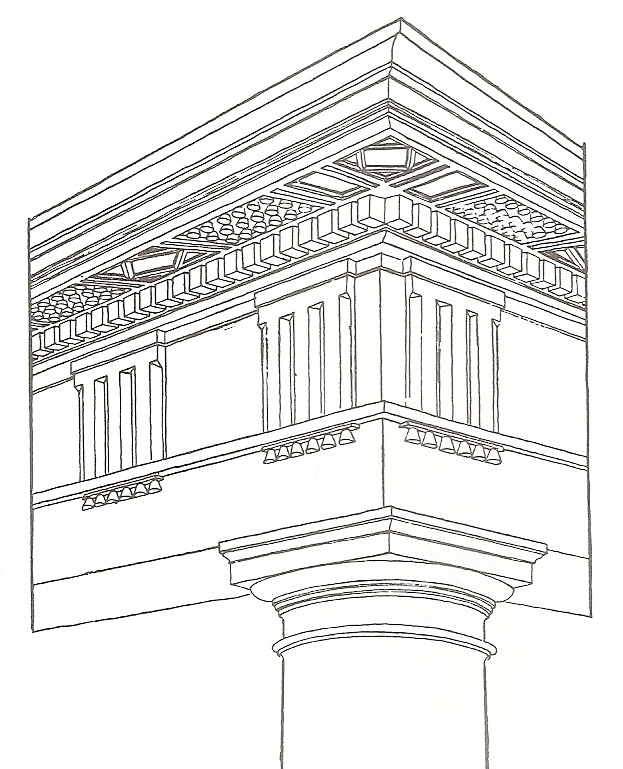

Neoclassical: monumental works with limited ornamentation and strict conformity to the canon of classical Greek and Roman architectural orders.

Neoclassicism flourished in New England from the late 1700s through the 1800s as the young republic sought to establish its legitimacy in the civilized world.

The grandeur and monumentalism of the Neoclassical style attested to its builders' sobriety, worthiness and seriousness of purpose, and America's fitness to sit in council with other, older countries more directly linked to the classical age.

Unlike the Greek Revival style, which borrowed certain elements from classical architecture, Neoclassicism demanded strict adherence to the Greek and Roman aesthetic. The classical orders, and particularly the sober, severe Doric order, were preferred. Geometric forms were simple, walls were often blank, and columns were used for dramatic effect.

Courthouses, libraries, government buildings and similar worthy edifices were thus given gravitas, but Neoclassicism was not limited to the more lofty purposes.

The Doric order, foundation of Neoclassical architecture.

The Doric order, foundation of Neoclassical architecture.

Late 19th-century styles

The Industrial Revolution saw the adaptation of Federal style to the design of huge factories, some a mile long.

New England has water power from its hundreds of creeks and rivers.

Great textile mills were built along New England's rivers during the first half of the 19th century, their looms driven by the swift currents. Only in the latter 1800s did steam power take over from water power.

The Federal style, so common in New England domstic and public architecture, was adapted to industrial uses. The large, substantial, straightforward brick factories in the many "mill towns" such as Fall River, Lowell, and Marlboro, Massachusetts are function yet stately, the wealth-making palaces of their age.

In Manchester, New Hampshire, the great Amoskeag mills march along the riverbank for almost half a mile, an impressive symbol of the era when Manchester produced more cotton cloth than any other city in the world.

The mills may have been Federal style, but for their own residences, amusements and endowments the mill owners wanted something more demonstrative. As the 1800's wore on, New England's grandees employed Henry Hobson Richardson, the firm of McKim, Mead and White, and other designers to build worldly fantasies: Egyptian temples, Renaissance palaces, Romanesque temples and Gothic churches.

Trinity Church, at Copley Square in Boston, is a fine example of the period. Newport, Rhode Island's elegant mansions—many of them actually small palaces— demonstrate how this late-century exuberance would end.

Among the "common people," 19th-century architectural exuberance led to Victorian gingerbread, some of the best of which survives in the town of Oak Bluffs on Martha's Vineyard island in Massachusetts.

Amoskeag Mills in Manchester NH, a stupendous example of New England's fine brick factories.

20th-Century Styles

America took its rightful place in the world order during the twentieth century, as its architecture reflects. Eclectic is the word, with a few distinguished skyscrapers (and a few infamous ones).

Skyscrapers soared above the quaint old neighborhoods of Boston, Providence, and Hartford. Many were undistinguished, few had echoes of New England's past.

But among the great commercial towers were some of imposing form and striking originality: Boston's slender, mirror-covered John Hancock Tower and Hartford's glass ellipse.

Boston skyscrapers—mostly big boxes.